Szeged, Hungary — A previously unknown terrestrial snail species dating back 99 million years has been identified with the involvement of researchers from the University of Szeged, shedding new light on life during the Cretaceous period.

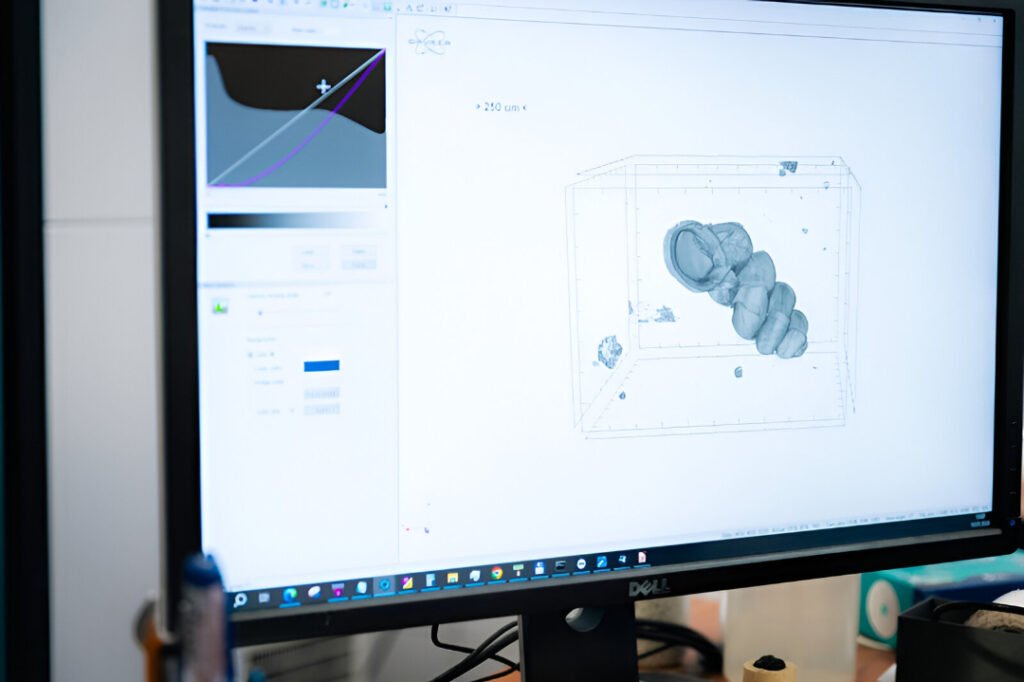

The fossil specimens, preserved in Burmese amber from Myanmar’s Hukawng Valley, were examined using high-resolution micro-CT imaging at the university’s Faculty of Science and Informatics. The work was carried out by Dr. Ákos Kukovecz, head of the Institute of Chemistry, and Dr. Imre Szenti from the Department of Applied and Environmental Chemistry, as part of an international research collaboration.

The amber — also known as burmite — is considered one of the richest fossil deposits in the world, having yielded exceptionally preserved remains of insects, spiders, amphibians and even dinosaur fragments. Scientists had previously documented around 30 snail species in burmite. The latest research expands that list with two newly identified species: Euthema convexispira and Euthema torokzselenszkyi, the latter named in honor of Hungarian musician and writer Tamás Török-Zselenszky.

The discovery was made possible by the university’s Bruker SkyScan 2211 micro-CT system, a state-of-the-art instrument capable of submicron resolution. The technology allows researchers to examine specimens non-destructively and reconstruct detailed three-dimensional models of organisms hidden inside amber. This level of precision made it possible to detect subtle morphological differences confirming that the fossils represented species previously unknown to science.

The Szeged team collaborated with researchers from Eötvös Loránd University, the Hungarian Natural History Museum, the HUN-REN research network, and the Natural History Museum of Colmar in France. Following scanning and analysis, the holotype specimen of Euthema torokzselenszkyi was transferred to the Hungarian Natural History Museum in Budapest, where it has become part of the permanent collection.

Beyond paleontology, the micro-CT system in Szeged supports research across materials science, energy storage, archaeology, dentistry and forensic science. The team has previously used the technology to study dinosaur jawbones, ancient wasps preserved in amber, ceramic manufacturing techniques, and even lithium-ion batteries under real operating conditions.

Researchers emphasize that such interdisciplinary collaboration is key to advancing discovery. By combining expertise in chemistry, paleontology and imaging science, the project demonstrates how cutting-edge instrumentation can uncover details invisible to traditional light microscopy.

The findings not only contribute to understanding biodiversity during the age of dinosaurs, but may also help scientists trace evolutionary patterns — including how terrestrial species adapted and thrived millions of years ago.

With further developments underway, including the launch of a new cryo-electron microscopy center at the University of Szeged, researchers say imaging-based innovation will continue to drive discoveries that connect the deep past with modern scientific progress.

Source: University of Szeged